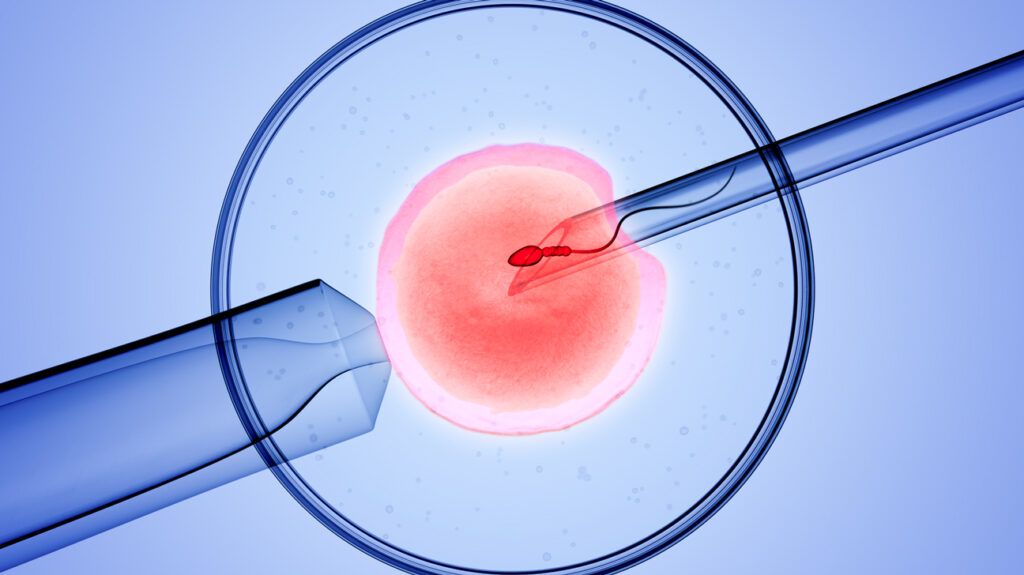

The past three decades have seen a steady increase in vitro fertilisation (IVF) success rates, and new research promises to push numbers even higher. But a surprising barrier stands in the way of innovation: legislation. What do the experts have to say about the obstacles, and what can individuals do to boost their chances of growing their families?

When the first healthy baby conceived through in vitro fertilisation — IVF, for short — was born in

Most societies hold higher birth rates as a positive sign — and as more and older individuals are turning to IVF to grow their families, there is more pressure than ever on researchers to find ways to increase its success rate.

Despite this, advancements in fertility technology are slow, and not just because good science takes time. Experts in the field say that outdated laws make it unreasonably difficult to perform research.

In the United Kingdom, there has been no update to legislation since 1990, and in the United States, a patchwork system of confusing state-by-state regulations vastly limit research options.

In this Special Feature, Medical News Today looks at how legislation hinders further advances in IVF research, what some exciting ways forward might be, and what individuals can do right now to improve their chances of embarking on a successful IVF journey.

In the 1980s and ’90s, IVF technology was new and heavily stigmatized. And while much of that stigma has now subsided, the legislation written during that time’s heavy restrictions still remain, and they stand in the way of quicker and more innovative research.

The British Fertility Society (BFS) is campaigning to change things, but progress is slow. Treasurer for the BFS and Director of Embryology at Bridge Clinic London Marta Jansa-Perez, PhD, feels that updating this legislation is essential to move IVF forward.

At present, the law is very restrictive on the use of embryos in research. “There’s a lot of very good researchers […] but there is a shortage of material for them,” she told Medical News Today. “The law has to change and allow patients to consent to generic research projects, and that would allow us to understand how embryos develop.”

The BFS is aiming to simplify time consuming and redundant consent forms, among other issues. They are also trying to make it easier for people to donate their embryos to research and streamline the process labs need to follow in order to acquire research licenses.

In the U.S., a convoluted state-by-state system means that embryo research is only legal in five states and “vaguely” legal in another 13, and a 1996 amendment banned the research from receiving federal funding.

And of the hundreds of thousands of unused frozen embryos in storage, just 2.8% are available for research.

Without easily available embryos to research, scientists often choose other avenues. A quick search-engine query shows a myriad of trials looking at everything from nutritional supplements to sound waves meant perk up “sluggish” sperm, but it is important to consider how much these factors can move the needle when it comes to IVF success rates — that is, to getting pregnant and having healthy babies.

According to Jansa-Perez, it takes a long time to gather evidence, analyze it, and determine how much a certain technology or lifestyle change could actually make a difference. And sometimes, enthusiastic retailers frame promising findings as proven results.

“There’s lots of things coming to market with limited research, and they’re being sold to patients before we have enough evidence,” she warned. “This is a field where we can sell a lot of things to patients and they will buy them because they’re desperate to do anything to increase their chances.”

One particular area of research that excites her though? The use of AI for selecting embryos.

Routinely, clinical embryologists select embryos based on morphology and using their own experience. New technology using AI models might be able to reduce subjectivity, save time, and increase success rates

“If you can make [that process] automatic and objective, that’s a great thing,” said Jansa-Perez. However, she noted that while the existent research excites her, we still have a ways to go.

“I think we need to continue developing the technology and doing proper trials to see if we can prove that those systems actually improve how we choose embryos,” she pointed out.

Using AI to choose embryos might raise success rates, but it also raises ethical questions. According to some recent research, the technology has moved faster than the ethical, social, and regulatory issues involved, and this might pose problems when it comes time to getting it approved for wider use.

Another exciting area of research threatens to completely revolutionize the landscape of IVF — but it is also a minefield of ethical dilemmas.

The very concept of

“If we were able to create artificial gametes that are healthy and viable, we might be able to revert the biological clock,” explained Jansa-Perez. They would also provide an exciting option for same-sex couples and people unable to produce viable eggs or sperm of their own.

However, experts note that this technology is far from ready and comes with a slew of potential issues.

“There is a lot of regulation on research involving human embryology, and most initial studies will be forced to work with animal models,” noted reproductive endocrinologist Kassie Bollig, MD, FACOG. “If it works here, it doesn’t necessarily mean it would work with humans,” she cautioned.

Scientists in Japan are currently studying this technology mice, and one of the researchers leading these efforts, Katsuhiko Hayashi, PhD, from Osaka University, predicts they will have a human egg to fertilize in 5–10 years, as he noted in a media interview.

But questions still remain. “Would they fertilize and grow into embryos? Would the quality of the embryos be good? The questions and ethical implications are endless,” said Bollig.

For her part, Jansa-Perez, was excited by the prospect of giving couples of all sexual and gender identities children that are genetically related to them, but noted that this is still far off: “It’s not for tomorrow.”

In the absence of scientific breakthroughs, is there anything people can do to increase their changes of getting pregnant via IVF?

Lifestyle factors

According to

- maintaining a moderate body mass index (BMI)

- eating a balanced diet

- taking folic acid

- exercising at a moderate intensity

- getting vaccinated

- avoiding tobacco and alcohol

- managing stress levels

- avoiding chemicals like pesticides and organic solvents.

Racial disparities

According to the Human Fertility and Embryology Authority (HFEA) report on ethnic diversity in fertility treatment, Black and asian parents had the lowest birth rates following IVF.

HFEA notes that age at treatment, underlying health conditions, and economic and structural factors are at play. However, sociocultural factors also contribute to the issue.

“There are issues with people feeling welcomed and recognized in certain fertility services when they see websites,” Jansa-Perez pointed out.

“I think it requires a cultural shift from the beginning, from the [family doctor] point all the way through.”

– Marta Jansa-Perez, PhD

She also noted that classifying people in boxes oversimplifies the issue: “We know that particularly Afro-Caribbean women have a higher incidence of fibroids, so it’s being aware of that, and perhaps looking at referring that population earlier on.”

Age and awareness

Most experts agree that the crucial factor is timing.

“Age is arguably the most important predictor of IVF cycle response and live birth potential,” said Bollig. And the research agrees: Birth rates gradually decline in older age groups, with those aged 18–35 having a 33% live birth rate and 43–50-year-olds having a rate of just 4%.

Even if you are not planning on getting pregnant yet, being aware of your fertility status and options is key.

As people start families later and later, being aware of potential fertility challenges ahead of time can empower people to make decisions that are right for them. For example, an ovarian reserve test can tell females how many eggs they have left.

Much like in other areas of life, when it comes to fertility, information is power.

“Communicat[e] the future desire for building a family, even if the goal is to not get pregnant now. One of the most common statements I personally have heard in my new patient consults is: ‘I wish I would have known this sooner.’”

– Kassie Bollig, MD, FACOG